Books

Book Recommendations and Reviews

Find Our Best Books of 2025 Here!

- Today in Books

Book Riot's best books of 2025 are here at last, the winner of Canada's Giller Prize, a misuse of CHARLOTTE'S WEB, and more.

Welcome to Today in Books, our daily round-up of literary headlines at the intersection of politics, culture, media, and more. And the Giller Prize Goes to… Souvankham Thammavongsa for a book I really want to read. Thammavongsa is now a two-time winner of the Giller, Canada’s prestigious literary prize awarding C$100,000 for excellence in Canadian fiction. The author’s most recent win is for her buzzy new novel, Pick a Color, while her 2020 win was for her short story collection, How to Pronounce Knife. As Publishers Weekly points out, numerous authors declined to have their books considered for the prize due to sponsors’ ties to Israeli arms manufacturing, defense, and settlements. Read more about the protests and the uncertain future of the Giller. Book Club Curators, come hang out in your new favorite corner of the internet! All book club organizers are invited to join the Book Club Curators Community over on Edelweiss. Members can connect over favorite reads, share new picks and ideas, and discover the latest and greatest from publishers. Whether you are planning your first discussion… or your hundredth, there’s something in the Community to inspire your best book club yet. Join here to get in on the fun! Keep Charlotte’s Web Out Your Mouth Martha White, the granddaughter of Charlotte’s Web author E.B. White, clapped back at the Trump administration after the Department of Homeland Security announced the launch of “Operation Charlotte’s Web” in North Carolina. In case you were confused, this operation is not an unlikely DHS kids reading program but a series of raids in Charlotte launched by federal immigration officials. A border patrol official quoted the following passage from the kid lit classic: “Wherever the wind takes us. High, low. Near, far. East, west. North, south. We take to the breeze, we go as we please.” Talk about spinning silver into crud. Martha White responded in a statement shared with CNN, saying her grandfather “certainly didn’t believe in masked men, in unmarked cars, raiding people’s homes and workplaces without IDs or summons. He didn’t condone fearmongering.” Hear hear. A New Sense and Sensibility I’m an Emma Thompson fan so Ang Lee’s 1995 adaptation of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility will forever be my one true adaptation, but that doesn’t mean I’m not going to put the upcoming Daisy Edgar-Jones version on my calendar. Edgar-Jones, also of that other notable adaptation, Normal People, will be our Elinor in the version directed by Georgia Oakley and scripted by Diana Reid. Call me basic, but I can’t get enough of the ubiquitous awkward advances and class friction in Austen’s most popular works, including this one. This story sits right up there with Pride and Prejudice for me. We’ll have to wait until September 2026 to see it in theaters, but I look forward to impending trailers. In the meantime, I leave you with this, because I don’t like to suffer alone: the Thompson Sense and Sensibility celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. Best Books of 2025 Picking the best books of the year was no easy task, but we sure had a lot of fun doing it. This year brought us romances that left us swooning, horror that made us sleep with the lights on, and magical stories that swept us away. It gave us memoirs that moved us, nonfiction that expanded our worldview, poetry to ground us when we needed it most, and so much more. We present you with our picks for the best books of 2025!The Best Nonfiction Books of 2025 What are you reading? Let us know in the comments!

Book Riot’s Deals of the Day for November 19, 2025

- Book Deals

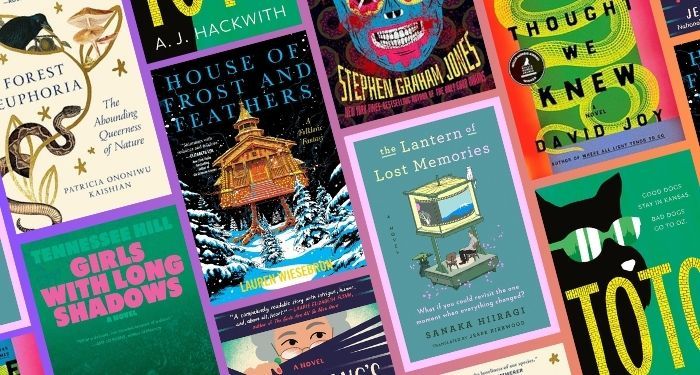

A very good literary dog, the abounding queerness of nature, rowdy wrestlers turned zombies, and more of today's best book deals.

Today’s Featured Book Deals $4.99 Forest Euphoria by Patricia Ononiwu KaishianGet This Deal $1.99 Vera Wong’s Unsolicited Advice for Murderers by Jesse Q. SutantoGet This Deal $1.99 House of Frost and Feathers by Lauren WiesebronGet This Deal $3.99 Zombie Bake-Off by Stephen Graham JonesGet This Deal $1.99 Toto by A. J. HackwithGet This Deal $1.99 Girls With Long Shadows by Tennessee HillGet This Deal $1.99 Those We Thought We Knew by David JoyGet This Deal $2.99 The Lantern of Lost Memories by Sanaka HiiragiGet This Deal In Case You Missed Yesterday’s Most Popular Book Deals $6.99 The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny by Kiran DesaiGet This Deal $1.99 Tiffany Aching Complete Collection by Terry PratchettGet This Deal $1.99 So Thirsty by Rachel HarrisonGet This Deal $1.99 Witches of Honeysuckle House by Liz ParkerGet This Deal

The Best Nonfiction Books of 2025

- Nonfiction

- True Story

There’s the story of a couple stranded at sea that has taken the nonfiction community by storm. And we can’t forget the memoir that is a love letter to reading.

Book Riot’s Best Books of 2025 list is finally here! The entire Book Riot team has selected books across genres to highlight, including a lot of nonfiction. There is a standout memoir from one of India’s greatest writers working today. There’s the story of a couple stranded at sea that has taken the nonfiction community by storm. And we can’t forget the memoir that is a love letter to reading. Get your TBRs ready! Mother Mary Comes to Me by Arundhati Roy By the time she won the Booker Prize for her debut novel, The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy had already lived several lives. Here, she recounts experiences as a poet, activist, architecture student, and award-winning novelist, but the real magic is in Roy’s reflections on the complex and ever-changing dynamics of family, relationships, and ambition. You needn’t know a thing about her career to find inspiration and intellectual delight in these pages. —Rebecca Joines Schinsky A Marriage at Sea by Sophie Elmhirst When you promise to love your partner “in good times and in bad,” you’re probably not imagining that the bad times will include 117 days lost at sea in a tiny lifeboat with a dwindling food supply and no way to call for help. In 1973, Maurice and Maralyn Bailey accidentally put their vows to the test when a whale rammed a hole into the yacht they were sailing from England to New Zealand. This is the gripping and unforgettable tale of how they endured illness, dehydration, near-starvation, and every emotion on the spectrum and managed to stay married for decades after. It’s an unbelievable story masterfully told. —Rebecca Joines Schinsky All access members continue below for more of the best nonfiction books of 2025. This content is for members only. Visit the site and log in/register to read.

2025’s Best Mystery, Thriller & True Crime Books

- Mystery/Thriller

- Unusual Suspects

Included are a retired elderly serial killer, an 18-year-old who survives a bomb explosion and learns her past is not what she thought, and more!

At the start of July, I hit you with part one of 2025’s Best Mystery, Thrillers, and True Crime selections, and now it’s time for the second half of the list! I still 100% stand behind my first set of picks, so if you forgot them or want to see them for the first time, definitely check those out too. As for the second part of the list, I am here once again with a few selections picked from Book Riot’s big Best of 2025 list (which also overlaps with my list!) and then more of my personal favorites. At the time of writing this, I’ve read more than 200 books this year, and 61% of them have been in the mystery, thriller, and true crime genres. My favorites this year include a retired elderly serial killer, a woman obsessed with buying a house, an 18-year-old who survives a bomb explosion and learns her past is not what she thought, and more! From Book Riot’s Best Books of 2025 This Place Kills Me by Mariko Tamaki, Nicole Goux (illustrator) This sapphic YA graphic novel takes place in the ’80s, but its story of teenage alienation is timeless. Wilberton Academy’s resident It Girl, Elizabeth Woodward, is found dead the morning after she starred in the school’s rendition of Romeo and Juliet. She’s said to have died by suicide, but something about that doesn’t feel right. Outcast Abby Kita is determined to find out what really happened to one of the few girls at Wilberton who was ever nice to her. Turns out, Elizabeth had secrets—secrets that might have gotten her killed. —Erica Ezeifedi Salt Bones by Jennifer Givhan A perfectly blended family drama with a past and present missing person’s mystery that sinks readers into a small town by the Salton Sea. I was equally invested in Mal and her family—from her mother blaming her for her sister’s disappearance when they were in high school to Mal keeping the father of her teen daughter’s identity a secret—and finding out what happened to the missing women, then and now. Throw in nightmares about a horse-headed woman, a politician brother aligned with the rich, and a race to find another missing person, and this atmospheric mystery is all-absorbing. Bonus: Victoria Villarreal is an excellent audiobook narrator. The Scammer by Tiffany D. Jackson I was still preaching the gospel of The Weight of Blood when I got around to reading The Scammer, and let me tell you, Tiffany D. Jackson does not, cannot miss. I was engrossed from the moment I saw where this story was headed (it’s inspired by the events surrounding the Sarah Lawrence cult, but set on an HBCU campus), and the ending left me in open-mouthed appreciation of a well-executed twist. If you like suspenseful books set on college campuses, explorations of cult dynamics and manipulation, and stories ripped from the headlines, you’re going to want to read this one now. —Vanessa Diaz More of My Favorite Mystery, Thrillers, & True Crime of 2025 All access members continue below for more of the best mystery, thriller, and true crime books of 2025 This content is for members only. Visit the site and log in/register to read.

The Best Comic Books and Graphic Novels of 2025

- Comics/Graphic Novels

- The Stack

2025's best comics and graphic novels will make you laugh, cry, and everything in between — in this year or any other!

Book Riot has released its Best Books of 2025! Hit that link to check out the main list, but not before you scroll down to see our picks for the year’s best comics…some of them, at least. You can’t begin to imagine the time I had keeping this list short, and how painful it was to make cuts. In any case, here are just a few of the amazing graphic novels released this year. They’ll make you laugh, cry, and everything in between — in this year or any other! Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes and Setor Fiadzigbey I knew this would be a difficult read, and I was right — but it is also incredibly powerful, moving, and even uplifting in the end. At just 12 years old, Jerome is shot and killed by a white police officer for playing with a toy gun. Jerome’s ghost meets other Black boys murdered by fear and racism, and makes an unlikely connection that could save other boys from becoming ghosts before their time. It Rhymes With Takei by George Takei, Harmony Becker, Steven Scott, and Justin Eisinger I included this one on my Best Books So Far list back in July, and it’s still here for good reason! Whether you’re a Trekkie or not, you’re sure to enjoy following along on Takei’s journey from aspiring actor to political activist to true legend (though yes, there are some funny Star Trek stories in here). Lu and Ren’s Guide to Geozoology by Angela Hsieh One of my favourite books of all time is The Tea Dragon Society by K. O’Neill. I’ve been searching for a book that is as comforting and beautiful as that one, and I’ve finally found it. When Lu stops getting letters from her ah-ma, the famous geozoologist, she and her best friend set out on a trip to find her, learning more about geofauna along the way. This queernorm middle grade fantasy graphic novel is a cozy story that also deals with grief and cultural divides between generations. The illustrations are so stunning that I finished the book and immediately ordered several art prints, which are now proudly displayed on my wall. —Danika Ellis More Weight by Ben Wickey “Epic” is the only word that truly encapsulates this graphic novel. Revealing the oft-forgotten human tragedies behind the sensationalized Salem Witch trials, More Weight explores the full horror of the trials themselves and the many ways that American society still struggles to deal with the consequences. This Place Kills Me by Mariko Tamaki and Nicole Goux This sapphic YA graphic novel takes place in the ’80s, but its story of teenage alienation is timeless. Wilberton Academy’s resident It Girl, Elizabeth Woodward, is found dead the morning after she starred in the school’s rendition of Romeo and Juliet. She’s said to have died by suicide, but something about that doesn’t feel right. Outcast Abby Kita is determined to find out what really happened to one of the few girls at Wilberton who was ever nice to her. Turns out, Elizabeth had secrets—secrets that might have gotten her killed. —Erica Ezeifedi For more great comics and graphic novels, take a look back at the books we were loving by the middle of the year with our Best Books of the Year (So Far) list.

Historical Best Books of the Year

- Historical Fiction

- Past Tense

Have you read the best historical fiction books of the year?

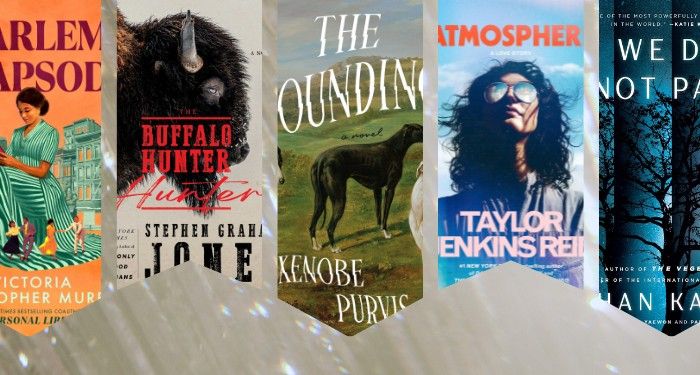

Determining the best books of the year is always an incredibly difficult challenge. How can you possibly narrow down hundreds of incredible releases into one, succinct list? Well, this year I did it with the help of my fellow Book Riot writers in our big Best Books of 2025 list, and I’m using their opinions again here to put together a shorter list of 2025’s best historical fiction. I may not be able to read every book out there, but between all of us, we do a pretty darn good job of narrowing that margin down some. So, these five titles are the best historical fiction books of the year, and that’s not just my opinion. At least three other Riot writers agree with me! My Favorites The Hounding by Xenobe Purvis When the townspeople of an eighteenth-century English village decide that a quiet, reclusive family of five sisters is hiding a magical secret, their fervor ignites into a terrifying fury. What gives them the right, and, moreover, what are the townspeople going to do about it? The Hounding is an incisive exploration of how hard times and herd mentality can transform prejudice and small-town gossip into real-life violence. What could happen then still happens now. Consider Pruvis’s haunting novel a primer on how not to treat your neighbor. Atmosphere by Taylor Jenkins Reid If Daisy Jones brought you to Taylor Jenkins Reid and Evelyn Hugo made you love her, then Atmosphere can only be described as Taylor Jenkins Reid at her very best. It’s a romance and a character study, exploring what life was like during a particular moment for a very particular set of people: queer women working on the space shuttle program at NASA in the 1970s and 80s. It’s beautiful, moving, and, at times, heart-stopping. Whether describing moments of Joan’s life in triumph or disaster, Reid will have you wrapped around her finger. You won’t be able to look away—and you’d never want to. —Rachel Brittain Rioter Favorites The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham Jones On the third day of reading Jones’ latest horror novel, I had a nightmare, but it might not be why you think. The monsters here are supernatural and all-consuming, but the true horror is the very real story that’s told of the Marias Massacre, where around 200 Blackfeet were murdered in the dead of winter. The story is told through a journal found in 2012, which was written in 1912 by a Lutheran pastor. The pastor records his time with a Blackfeet man named Good Stab, a man with peculiar eating habits and seemingly superhuman abilities… and revenge on his mind. —Erica Ezeifedi Harlem Rhapsody by Victoria Christopher Murray This Harlem-set, Jazz Age historical novel tells the story of the nearly forgotten Jessie Redmon Fauset, who changed the course of Black American literature and American literature as a whole. She made history as the first Black woman Editor of The Crisis, the oldest Black magazine in the world, and became known as “The Midwife of the Harlem Renaissance” because of her discovery and mentoring of writers like Langston Hughes and Nella Larsen. She wasn’t without her drama, though—it was well-known that she and her very married boss, W.E.B. Du Bois, were carrying on in the Biblical sense. And this book dives headfirst into the mess. —Erica Ezeifedi We Do Not Part by Han Kang, translated by E. Yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris Literary fiction of the highest order from a Nobel Prize-winning novelist. Not much happens in this quiet, dream-like novel that asks rich questions about history, memory, connection, and pain. It’s the rare book that can be equally subtle and unsettling, and that’s evidence of a masterful writer working at the height of her powers. You always know you’re in good hands with Kang, and that makes it a pleasure to follow her wherever she wants to go. —Rebecca Joines Schinsky Be sure to check out our picks for the best historical fiction of 2024, 2023, and 2022 as well, and if you’re craving even more distant backlist fiction, try the best historical fiction books from the last 10 years and the best historical fiction of the century (so far).

New YA Book Releases for November 19, 2025

- What's Up in YA

- Young Adult Literature

From a royal murder to a queer K-pop take on Jane Austen, read your way into this week's new YA book releases.

We’re really hitting our downhill slide to the end of the year in the world of new young adult book releases. Where it was once difficult to pick and choose which titles to highlight each week, this week and next week’s choices are much less difficult simply because there are fewer titles. Because of the Thanksgiving holiday in the U.S. next week, this week’s new releases also include titles hitting shelves then. I’ve indicated which titles those are with the publication date beside them; any books without a date next to them are available this week. On deck this week are a fun K-pop take on Pride and Prejudice, a story of a girl finding her place in roller derby, a short story collection set in the world of a popular series by a beloved YA author, and so much more. This week, we’ve also got another pair of book doing simultaneous releases in paperback and hardcover. I suspect that will continue to happen with frequency into the new year, and it’s a much-needed publishing trend that allows readers to pick the format that best fits their needs (and their budgets!). Note that this week’s releases are not as diverse as usual, and that’s a product of fewer releases hitting shelves. That said–and as noted before–there is some fear that we’ll begin to really see fewer diverse titles beginning next year due to the ongoing attacks on books by or about marginalized people. It’s our responsibility to watch what’s happening in publishing and call it out if this fear begins to bear out. New Hardcover YA Releases This Week The Cuffing Game by Lyla Lee In this K-Drama remix of Pride and Prejudice with queer lead characters, readers who love reality TV and YA books with older teens will find a lot to like. Mia got a full ride to film school behind her mom’s back, and it’s her way out of an unfulfilling small town life. She’s now working to produce a dating show, but all of her plans are challenged when she’s forced to ask her secret crush Noah to help her. She’d much rather just hate him instead. Noah’s one of the most eligible bachelors on campus, and despite pressure from his peers, he’s okay with that. He doesn’t need a relationship right now. But his eyes are on Mia, and he’s delighted when she asks him to help her on her show. He’ll be one of the eligible contestants. But watching Noah go on dates from behind the scenes isn’t sitting well with Mia. And those feelings are reciprocated by Noah, who wonders if he’s really meant to be dating the girl behind the camera. How Girls Are Made by Mindy McGinnis McGinnis’s latest novel is being pitched as Sex Education meets Euphoria and sounds like it tackles a whole lot of right-now issues in an intense and compelling way. The book follows three girls. There’s Fallon, a girl who thinks she’s got everything all figured out. But when her younger sister asks her a basic question about sex and Fallon realizes she doesn’t know the answer, she creates an off-campus group to get some practical answers. Shelby is a girl who fights, but things take a turn when her boyfriend hits her. After that happens, it’s a new guy who wants to court her. He’s saying everything right and flattering, and Shelby is willing to change some of the things he thinks could be better about her. Then there’s Jobie, who wants to be a social media influencer but never quite gets the traction she thinks she deserves. So when she gets a DM from someone who suggests an audience of open and receptive guys who’d be eager to help her career flourish. All three of the girls get to know each other in Fallon’s secret group. But while they all fight to achieve the things they think that they want, not all of them will get out of this alive. I’ll Find You Where the Timeline Ends by Kylie Lee Baker Yang Mina was born with the power to travel through time. This is because she is the descendant of a Japanese dragon god, and she’s spent her life preparing to join the Descendants. The Descendants are charged with protecting the timeline. There’s just one, err, many problems. Mina’s moved to Seoul and discovered that the Descendants are corrupt. That doesn’t touch upon her sister being literally erased from existence and her bad grades in calculus. It also doesn’t touch upon her dream of kissing the cutest boy in her class feeling more and more impossible. Mina has to do something. That something is teaming up with Yejun, a dangerous proposition, as he’s a rogue agent. But Yejun wants to help remove corrupt influence from the Descendants and he promises Mina he’ll restore her sister to the timeline. Mina and Yejun are meeting between classes in time travel dates, and all seems like it’s going well. At least, it did. Now Mina’s beginning to see the truth about Yejun, and all of his promises are sounding less and less, well, promising. New Hardcover Series Releases: Mindworks: An Uncanny Compendium of Short Fiction by Neal Shusterman–this one is releasing both in hardcover and paperback simultaneously. Wheel of Wrath by A. A. Vora More Hardcover YA Releases This Week: Heart Check by Emily Charlotte–this one is being released in hardcover and paperback simultaneously. Leave It On The Track by Margot Fisher New Paperback YA Releases This Week Out of Air by Rachel Reiss Phoebe “Phibs” Ray loves being underwater. It was only six months ago when she and her friends were on a dive and found some ancient gold coins. That gave them a rush of social media fame, even. Now it’s their final summer together before college and life post-high school, and Phibs and her friends are going to take one more dive together. Phibs finds an underwater cave on this dive, and it’s a cave rumored to have some sunken treasure. But when Phibs and her friend Gabe surface, strange things are happening to them. They’re hearing whispers in their head. They have wounds that aren’t healing. They’re being invaded from the inside out. Now treasure hunters have arrived, eager to find the bounty that Phibs and her friends think they may have stumbled upon. Those hunters plan to take the teens for ransom. But it won’t be long before Phibs and those wanna-be criminals discover the true monster lurking right beneath the surface. Red As Royal Blood by Elizabeth Hart Ruby loves a puzzle, but she was not prepared to put together why, when destined to the role of servant to the royal family, she was then named the heir to the throne before the king’s death. She’s now left to clean up an unbelievable mess. It begins with the king’s wife being angry. It continues with the king’s three sons being irate that they aren’t his successor. It only gets worse when she discovers a note from the king that he’s actually been murdered and that she, Ruby, will be next. To solve the king’s murder–to figure out if it was a murder at all–Ruby must work with the three princes. But her time is short because if they can’t figure out whether or not there’s a killer on the loose, her life may be the next one taken. New Paperback Series Releases: A Wild and Ruined Song by Ashley Shuttleworth–this one publishes next week, on November 25. More Paperback YA Releases This Week: Perfect Girl by Tracy Banghart Want more YA book recommendations? Of course you do. Here are some excellent recent queer takes on Jane Austen, as well as some of the biggest books of the fall.

A London-Set, Psychotherapist-Led Mystery That’s Perfect for Cold Weather

- Mystery/Thriller

- Read This Book

This series starter is a prime example of well-plotted mystery/thriller novels that have characters at their heart

The first time I listened to the Frieda Klein series, I was tucked in on the couch in my parents’ living room in front of the fire during the holidays. All of us had come down with colds and sat in commiserable silence as we drank hot chocolate and ate Christmas Day leftovers. For the entire week, I finished a novel a day—one of those days, I inhaled this engrossing story about a psychotherapist who begins consulting for the police. This fall, I felt the overwhelm of—well, everything—so instead of doomscrolling my mental health into oblivion, I returned to the world of Frieda Klein’s 2010s London. Blue Monday by Nicci French On an ordinary autumn day in London, Matthew Farraday disappears from his primary school. Soon, his face is plastered in every newspaper and news program. But the police have exhausted every lead and crumb of evidence. Enter Frieda Klein, a psychotherapist who spends her days listening to her patients describe their troubled lives and her sleepless nights walking the streets of London. When her new patient describes a fantasy where he has a son matching the description of Matthew Farraday, Frieda breaks confidentiality and takes her concerns to the police. Soon, she finds herself entangled in the case that will change her life forever. The eight-book series follows Frieda through several years as this first case haunts her every step. No matter how many cases she solves, it always comes back to the Matthew Farraday case. While every book in the series is fantastic, it’s Frieda and her band of friends that keep us coming back for more. Through every twist and turn, Frieda grows to rely on the people around her. As I reread the series, I began to realize how much foreshadowing and complex plot French includes throughout these novels. One of Klein’s greatest loves is London geography, which shows up from the start. She especially loves London’s many rivers, which end up playing a huge role later in the series. Frieda is an endlessly fascinating character, and her many secrets are revealed slowly, making you want to pick up the next book immediately. Great writing happens in every genre, and the Frieda Klein series is a prime example of well-plotted mystery/thriller novels that have characters at their heart. For me, late fall and early winter will always be Frieda Klein season. You can find me over on my substack Winchester Ave, over on Instagram @kdwinchester, or on my podcast Read Appalachia. As always, feel free to drop me a line at kendra.d.winchester@gmail.com. For even MORE bookish content, you can find my articles over on Book Riot.

6 of the Best Detective Characters in Fantasy Novels

- Mystery/Thriller

- Science Fiction/Fantasy

- Swords and Spaceships

From Harry Dresden to Acatl, High Priest for the Dead, here are six of the best detective characters in fantasy novels.

Hell-bent on avenging her parents’ murders, Saffron Killoran lies her way into Silvercloak Academy—a training ground for elite detectives—with a single goal: to bring the ruthless Bloodmoons to justice. But when Saff’s deception is exposed, she’s given a rare opportunity: to go undercover and tear the Bloodmoons down from the inside. Descending into a world where pleasure and pain are the most powerful currencies, Saff must commit some truly heinous deeds to keep her cover—and her life. Each day tests her loyalties further—and one false step could destroy everyone she’s ever loved. I always enjoy when genres collide. Like when a fantasy creature unleashes its magic on a futuristic sci-fi society, or when a lovely romance finds its way into a horror novel. This particular post is about the merging of genres, too: when the detective of crime fiction enters a fantasy setting. Sleuthing amidst dragons and spells? Yes, please, and thank you. In this post, I’ll go over some of the best detectives in fantasy novels. That said, I want to make a little aside and clarify what I mean by detective here. Sometimes they’re a jaded PI or homicide detective, yes, but just as often they’re a normal person who finds themself thrust into a mystery and breaks out the detective-ing skills to solve it. Because let’s be real, professional detectives are amazing, and literature would not be the same without them (please don’t ever leave me, Monsieur Poirot), but someone beating the odds and solving the mystery when they’re not professionally trained to do so? Amazing. Spectacular. 10/10, no notes. I chose a mix of famous and lesser-known detectives from fantasy fiction, not necessarily because they are indisputably better than every other fantasy detective (that would be a tall order, considering the breadth and scope of the genre), but because I wanted to give an overview. If you’re not familiar with detectives in fantasy, this is a good place to start. Happy reading! October “Toby” Daye from Seanan McGuire’s October Daye series October “Toby” Daye is a changeling: a child born to a human and a fairy. Don’t let that fool you: that doesn’t make her life perfect and magical. On the contrary, since mortal halfbreeds aren’t exactly loved by the Fae, she tries her luck in the human world, which turns out to be… a disappointment, to say the least. Eventually, a murder drags Toby right back to the world of the Fae, where she has to balance solving the case and staying alive. Start with: Rosemary and Rue. Harry Dresden from Jim Butcher’s Dresden Files series Who doesn’t love Harry Dresden? A professional wizard and private investigator based in Chicago, Harry has an impressive backstory and, more importantly, a great skill for solving cases, many of which are of the supernatural variety. Start with: Storm Front. Acatl, High Priest from the Dead, from Aliette de Bodard’s Obsidian and Blood series This series follows Acatl, High Priest for the Dead, as he splits his time between seeing to the funeral rites of the Aztec Imperial Family and investigating less mystical matters. Set in Tenochtitlan, I admit I had not heard of this series before beginning my research on this post, but you better believe I will fix that ASAP. Start with: Servant of the Underworld. Yusuke Urameshi from Yoshishiro Togashi’s YuYu Hakusho series I’ve mostly featured prose fantasy novels here, but I’m including this manga series because it’s still very much fantasy and because I refuse to leave Yusuke Urameshi out of this list. He is a belligerent teenager who, upon his death saving another child, is given the chance to return to life. Once back, he is given the title of Underworld Detective and told to investigate supernatural activity in the human world. Start with: Goodbye, Material World! Garrett from Glen Cook’s Garrett P.I. series Remember when I talked about genres colliding? This is a straight-up detective story taking place in a fantasy setting. Garrett is a freelance private investigator whose work takes him all over the kingdom of Karenta, a place where anti-human racism runs rampant. Start with: Sweet Silver Blues. Bree Matthews from Tracy Deonn’s The Legendborn Cycle series This YA series had me at “Arthurian legend”. Sixteen-year-old Bree Matthews is trying to cope with her mother’s death when she enrolls in a prestigious program at UNC-Chapel Hill. But the discovery of magic, a secret society, and the knowledge that there might have been more to her mother’s death than meets the eye all force Bree to embark on a quest to find out what exactly happened. Also, did I mention that she uncovers her own magic in the process? Start with: Legendborn. If you can’t get enough of fantasy, why not take a look at 10 of the best magic systems in fantasy? Or, if mysteries are more your thing (and you’re done with 2025), look forward to these 2026 mysteries & thrillers!

Best Books of 2025

- Best Books

- Events

- Featured

- Riot Headline

Picking the best books of the year was no easy task, but we sure had a lot of fun doing it. We present you with our picks for the best books of 2025!

Picking the best books of the year was no easy task, but we sure had a lot of fun doing it. This year brought us romances that left us swooning, horror that made us sleep with the lights on, and magical stories that swept us away. It gave us memoirs that moved us, nonfiction that expanded our worldview, poetry to ground us when we needed it most, and so much more. We present you with our picks for the best books of 2025! A Guardian and a Thief by Megha Majumdar Fiction In the near future in Kolkata, India, a family prepares to immigrate to the United States as climate refugees. When a thief breaks into their home in search of food, his life becomes inextricably entwined with theirs as, over the course of one week, they all struggle to survive with their hope and humanity intact. It’s a powerful story made all the more urgent by Majumdar’s use of subtle, specific details and masterfully restrained writing. Nominated for the Kirkus Prize and National Book Award for Fiction, this is a story about a specific moment in history that will resonate for years to come. - Rebecca Joines Schinsky Buy Now A Marriage at Sea: A True Story of Love, Obsession, and Shipwreck by Sophie Elmhirst Autobiography/Biography/MemoirNonfiction When you promise to love your partner “in good times and in bad,” you’re probably not imagining that the bad times will include 117 days lost at sea in a tiny lifeboat with a dwindling food supply and no way to call for help. In 1973, Maurice and Maralyn Bailey accidentally put their vows to the test when a whale rammed a hole into the yacht they were sailing from England to New Zealand. This is the gripping and unforgettable tale of how they endured illness, dehydration, near-starvation, and every emotion on the spectrum and managed to stay married for decades after. It’s an unbelievable story masterfully told. - Rebecca Joines Schinsky Buy Now A Sharp Endless Need by Mac Crane Fiction Mack Morris lives for basketball, but after their father’s death, the game can’t fill the void. Despite being recruited to a top college, Mack feels lost. Then, Liv Cooper transfers to their team. Before long, their chemistry burns on and off the court. Mack hides their feelings, but desire keeps resurfacing. Crane captures longing and tension with poetic precision, turning basketball into a dance of longing. Mack’s doubts about college, the pros, and their own identity drive them toward self-destruction through substance abuse. Even for non-sports fan readers, Crane’s prose makes the rhythm and beauty of the game pulse on every page. - Kendra Winchester Buy Now A Witch’s Guide to Magical Innkeeping by Sangu Mandanna FantasyRomance Sangu Mandanna’s first adult romance, The Very Secret Society of Irregular Witches, was acclaimed for its warm, immersive style, and Mandanna – facing all the challenges of delivering a follow-up – could have decided to go a completely different direction with her next book. Instead, she doubled down and provided another cozy novel about found family, this time centered on a witch who’s lost her magic and an inn that calls to those who need it most. Mandanna realizes that “cozy” doesn’t mean a lack of pain or emotion but rather ensuring that a character dealing with those things is offered love and support. And sometimes an undead rooster. - Trisha Brown Buy Now Along Came Amor by Alexis Daria Romance Ava is a divorced middle school teacher. Roman is a self-made and, somehow, ethical billionaire hotel owner. A chance meeting leads to a one night stand. But then Ava finds out that Roman is the best man in her cousin’s wedding, and she is the maid of honor. Roman is delighted and clears his schedule to accompany Ava to Puerto Rico to help organize the wedding. But Ava isn’t so sure. She’s feeling wounded from her divorce, pressure from her family, and unable to trust anything—even her own feelings. I am a former teacher and people pleaser, so I loved seeing Ava work through her complex emotions to get the fantasy romance she deserved! - Alison Doherty Buy Now Atmosphere by Taylor Jenkins Reid Fiction If Daisy Jones brought you to Taylor Jenkins Reid and Evelyn Hugo made you love her, then Atmosphere can only be described as Taylor Jenkins Reid at her very best. It’s a romance and a character study, exploring what life was like during a particular moment for a very particular set of people: queer women working on the space shuttle program at NASA in the 1970s and 80s. It’s beautiful, moving, and, at times, heart-stopping. Whether describing moments of Joan's life in triumph or disaster, Reid will have you wrapped around her finger. You won't be able to look away—and you’d never want to. - Rachel Brittain Buy Now Audition by Katie Kitamura Fiction Kitamura starts us out with a tight and masterful portrayal of people playing roles, and thinking about playing roles. Then, at about the halfway point, the stakes are changed, not in terms of register but in terms of what stories are and can do. Like many novels that contest and break expectations, Audition is not a general-purpose recommendation. (I would expect it to have the lowest Goodreads star rating of any book on this list, for example). But for readers who are interested in what else is possible in a book, or hell, what else is possible in a life, Audition is something other than satisfying—it is confounding, provocative, and new. - Jeff O'Neal Buy Now August Lane by Regina Black Romance This brilliant literary romance is a powerful reminder that Black country artists have always been here. One-hit-wonder Luke is honored to open for his idol, 90s superstar JoJo Lane, at her induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame. But he’ll have to confront his complicated past, because the concert is being held in his and JoJo’s small hometown in Arkansas. Luke was close to JoJo’s daughter, August, until a shocking betrayal ripped them apart and jump-started his career. As Luke, August, and JoJo grapple with their complicated relationships to the music industry, a new love song takes shape. It’s fantastic in any format, but I recommend the full-cast audiobook. - Susie Dumond Buy Now Automatic Noodle by Annalee Newitz Science Fiction All the coziness and character of a Becky Chambers novel with the wit and charm of Martha Wells. I never knew I needed a book about robots running a restaurant in a near-future San Francisco, but Automatic Noodle proved I did. I would die for these robots—or at least leave them lots of really, really good reviews. - Rachel Brittain Buy Now Awakened by A.E. Osworth Fantasy When I heard that Awakened was about a coven of trans witches that fight an evil AI, it immediately rose to the top of my most-anticipated list. I'm happy to say it lived up to those expectations, from its dedication—"For everyone who feels betrayed by J.K. Rowling"—to its final page. The whimsical narrator makes for a fun contrast to the cynical main character, reluctantly adjusting to their new powers. Each of the members of this coven is complex and multifaceted, making their slow progression into a chosen family feel satisfying and realistic. Yes, this is a fantastic read for ex-Harry Potter fans, but it's so much more than that. - Danika Ellis Buy Now Bat Eater and Other Names for Cora Zeng by Kylie Lee Baker Horror This is the book I cannot stop recommending or talking about. In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Cora’s sister was pushed in front of a train. Cora continues to clean up gruesome murders in Chinatown while Delilah’s assailant’s last words, “Bat Eater,” ring in her ears. The mutilated bats at every scene only heighten Cora’s suspicions that the attack on Delilah wasn’t random. Cora struggles with compulsions and her grief only grows as she begins to notice signs of Delilah everywhere. She turns to her remaining family and her coworkers for help to free Delilah from becoming a hungry ghost forever. Somewhere between horror and murder mystery, Bat Eater is a ghost story for 2025. - Courtney Rodgers Buy Now Best Woman by Rose Dommu Fiction Family weddings are never easy, but Julia’s brother’s is a particular kind of minefield. Since leaving Florida, she’s transitioned and is living her best, queerest life in New York. The references to iconic rom-coms are threaded throughout, but this still feels fresh and original. While Julia’s navigating the minefield of best woman duties for her brother, she encounters a former crush, Kim. Julia re-connects with Kim over a lie, but the genuine spark between them is impossible to deny. Dommu also retains her extremely pithy, irreverent Internet voice, expertly translated into long-form prose. Whatever rom-com she tackles next, I’m there. - Julia Rittenberg Buy Now Blob: A Love Story by Maggie Su Fiction You don't have to like Vi to empathize with her experiences as a college dropout living in a Midwest town where she sees herself having no future. But you will certainly be unable to stop reading this book after she discovers a blob on the street and brings it home. This is no ordinary blob, though. It's sentient, and over the course of the story, it begins to grow limbs and a whole personality. Vi realizes she has an opportunity here: make this blob her ideal partner and finally find true, meaningful love. Blob is a weird, funny, and moving read about identity, family, and, err, street blobs. - Kelly Jensen Buy Now Bury Our Bones in the Midnight Soil by V.E. Schwab Fantasy Maria, in 1532 Spain, latches on to a rebellious marriage to try and get her freedom from all the restrictions placed on her; Alice, in 2019, hopes college will be a fresh start, and is thrilled to meet the mysterious Lottie. The three women unspool into a centuries-long story about how far these women will go in the name of their rage and their desire for freedom. Playing on the same fears and dramas of Interview With the Vampire with a brush of her hit The Invisible Life of Addie Larue, Schwab's newest gives readers richly painted, queer vampires caught in a multi-century web of obsession, immortality, and longing. - Leah Rachel von Essen Buy Now Cannon by Lee Lai ComicsGraphic Novel After Stone Fruit, I longed for Lai’s second graphic novel about Cannon, a cook, and Trish, a writer, from Lennoxville. Every week, the best friends—“on the uncool side of [their] twenties”—watch a scary film until distance threatens their bond of 14 years. Opening in a trashed Montreal restaurant with a regretful Cannon, the story returns to three months prior. Featuring mostly black-and-white art, I devoured this, obsessed with the use of color, horror influences, and complex relationships. As I reread this stunning meditation on breath, intimacy, and care, I observed what appears in red, which frames birds populate, and how they converge. - Connie Pan Buy Now Cults Like Us by Jane Borden Nonfiction Is America a cult? Borden explores this question by diving into the morals and beliefs that shaped Puritanical colonization. The book surveys a cult's characteristics, tracing how groups, laws, and policies throughout American history have led to conspiratorial thinking among its people. This includes why Americans are so susceptible to pyramid schemes; why most American cults have been white and politically right-leaning; and when such thinking has surged in this country's timeline. Engaging and enraging, this is the history and contemporary exploration of America we need right now. - Kelly Jensen Buy Now Death In The Jungle: Murder, Betrayal, and the Lost Dream of Jonestown by Candace Fleming NonfictionYoung Adult Jim Jones, leader of one of the most notorious cults in history, The People’s Temple, managed to convince 900 people to drink cyanide to their ultimate deaths. But how did he do it? This book traces Jones’s story from his youth growing up during the Great Depression to where and how he convinced people to follow him and his beliefs. You’ll follow Jones and his devotees from California to their off-grid Jonestown compound in the depths of Guyana. Fleming's research is deep, and the story is situated in the experiences of young people growing up within this cult. An example of knockout nonfiction for young adult readers (and beyond!). - Kelly Jensen Buy Now Deep Cuts by Holly Brickley Fiction I’m still surprised that the BookTok and Bookstagram girlies didn’t become obsessed with this book and hold onto it for dear life. Set in the 2000s, Deep Cuts follows Percy and Joe, two college students who meet at a bar one fall night and instantly bond over their love of music. What follows is a years-long, on-again-off-again relationship (or toxic situationship, if you will) and a creative partnership that always brings them together as passionately as it tears them apart. Full of all the awkward twentysomething behavior most of us would like to forget, Deep Cuts is an ode to the miracle of music and the art of getting by. - Jeffrey Davies Buy Now Don’t Trust Fish by Neil Sharpson, illustrated by Dan Santat Children's What starts as a nonfiction animal classification book takes a wild and hilarious turn when the narrator begins describing why readers should not trust fish. First off, there are massive variations between all the species who fall under this category (some fish are tiny while others are big as a bus … and that’s NOT okay). But more importantly, they might be plotting dastardly plans, such as shipwrecks or even world domination! The comedic timing and hyperbole in the text make this book incredibly fun to read out loud. And the illustrations, by the legendary Dan Santat, are equally important to the hilarity of this picture book. - Alison Doherty Buy Now Down in the Sea of Angels by Khan Wong FantasyScience Fiction This blending of science fiction and fantasy takes place in San Francisco along three timelines—two in the past and one in the not-too-distant future. The oldest timeline is in 1906 with Li Nuan, a teen who was sold to a San Francisco Chinatown mob boss to settle her father’s debts. Then in 2006 is a queer, Chinese American named Nathan, who works in tech and is a Burning Man devotee. Finally, the year 2106 is woven in with Maida Sun, a woman with psionic abilities. It’s a beautifully written and thought-provoking examination of our connections and obligations to each other through time. - Patricia Elzie-Tuttle Buy Now Flashlight by Susan Choi Fiction Susan Choi's sixth novel is a masterpiece, a family saga wrapped in a mystery that haunts its characters. Young Louisa and her father are walking along a beach at night, carrying flashlights. Hours later, Louisa is found alone, barely alive, and her father is never seen again. As Louisa grows up with her mother, the loss of her father hovering over their lives, parts of their pasts are revealed, including a long-held secret. Flashlight is a sharp examination of not only the physical loss of someone, but loss of place, estrangement, and loss of self, as Louisa and her mother carry around a grief with no end. It's a stunning heart-puncher. - Liberty Hardy Buy Now Harlem Rhapsody by Victoria Christopher Murray Historical Fiction This Harlem-set, Jazz Age historical novel tells the story of the nearly forgotten Jessie Redmon Fauset, who changed the course of Black American literature and American literature as a whole. She made history as the first Black woman Editor of The Crisis, the oldest Black magazine in the world, and became known as "The Midwife of the Harlem Renaissance" because of her discovery and mentoring of writers like Langston Hughes and Nella Larsen. She wasn't without her drama, though—it was well-known that she and her very married boss, W.E.B. Du Bois, were carrying on in the Biblical sense. And this book dives headfirst into the mess. - Erica Ezeifedi Buy Now Holler: A Graphic Memoir of Rural Resistance by Denali Sai Nalamalapu Autobiography/Biography/MemoirGraphic Novel Denali Sai Nalamalapu, a climate activist, brings the story of the Mountain Valley Pipeline and the people who resisted it to vivid life. Spanning 300 miles through West Virginia and Virginia, the pipeline cut through farms and forests, devastating land. Nalamalapu spent hours with activists, organizing their experiences into six illustrated chapters. Each one depicts small but powerful acts of defiance, like Becky Crabtree chaining herself to her Bronco or Monacan seedkeeper Desirée Shelley preserving her community’s future. With its intimate storytelling, Holler shows how collective, everyday resistance can protect both land and hope. - Kendra Winchester Buy Now I Got Abducted By Aliens and Now I’m Trapped in a Rom-Com by Kimberly Lemming RomanceScience Fiction When it comes to whimsy, irreverence, and outright silliness, Kimberly Lemming is That Girl. In her first sci-fi romance that takes the teeniest amount of inspiration from The Wizard of Oz, a grad student who just wants to complete her research and write her dissertation gets kidnapped by aliens alongside the lion that’s about to eat her, and it just gets more wild from there. Whether it’s about proper academic research, the lines of consent with regard to genetic programming, or trying to make Only One Bed happen when there are plenty to choose from, this book talks about both the serious and the silly in the most hilarious way. - Jessica Pryde Buy Now Katabasis by R.F. Kuang Fantasy While this book is more divisive than I predicted, I remain a fan and see it as yet more evidence of Kuang's versatility and willingness to take risks as a writer. This is dark academia with an emphasis on the academic, pulling concepts from linguistics, math, and religion to explore the afterlife as only Kuang can. I might be biased as fiction about this realm of the unknown is deep in my wheelhouse, but it's also pretty hard to make a dark academia fantasy stand out from the swiftly-growing category. Katabasis does. It was also compelling enough to attract Hollywood's attention with an adaptation already in the works. - S. Zainab Williams Buy Now King of Ashes by S.A. Cosby Mystery/Thriller Nobody is writing crime novels like S.A. Cosby is writing crime novels. In King of Ashes, Roman Carruthers has "made good" and left his Virginia hometown for Atlanta. He comes home following an accident that left his father in a coma to find his brother is in deep debt to dangerous people. How far will Roman go to protect his family? The backdrop of the family crematory business provides an atmosphere of omnipresent death and suffocating heat. Meditating on systemic racism and generational trauma, this unflinching book has complex characters that don't easily fit into archetypes and prose so sharp it could draw blood. - Isabelle Popp Buy Now Lessons in Magic and Disaster by Charlie Jane Anders Fantasy This book was such a balm this year with themes of family, community, and love, but mostly Anders’s remarkable ability to make readers believe that magic and healing are within reach for all of us. Jamie is a grad student in New England who is incredibly stressed as she tries to nail down a dissertation that continues to slip through her fingers. Adding to her stress is her relationship with her mother Serena, who has been grieving the loss of her wife and living as a hermit in an old schoolhouse for years. Jamie is also a witch and decides that teaching her mother magic is a great idea to reconnect, yet this goes sideways quickly. - Patricia Elzie-Tuttle Buy Now Lu and Ren’s Guide to Geozoology by Angela Hsieh Children'sComicsFantasyGraphic Novel One of my favourite books of all time is The Tea Dragon Society by K. O'Neill. I've been searching for a book that is as comforting and beautiful as that one, and I've finally found it. When Lu stops getting letters from her ah-ma, the famous geozoologist, she and her best friend set out on a trip to find her, learning more about geofauna along the way. This queernorm middle grade fantasy graphic novel is a cozy story that also deals with grief and cultural divides between generations. The illustrations are so stunning that I finished the book and immediately ordered several art prints, which are now proudly displayed on my wall. - Danika Ellis Buy Now Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson by Tourmaline Autobiography/Biography/MemoirNonfiction This is a deeply researched, definitive biography of transgender activist and artist Marsha P. Johnson. Written by the brilliant multi-hyphenate Tourmaline, this beautifully written book shows Marsha as a whole person, both before and after the Stonewall Uprising of 1969. Many people have heard that Marsha threw the first brick during the Stonewall Uprising, but few people know much beyond that. She was an artist and performer who toured outside of the U.S. She was a poet and muse and a fierce friend bursting with love. This book also includes some gorgeous photographs and is told with the care and reverence that Marsha’s story deserves. - Patricia Elzie-Tuttle Buy Now Mother Mary Comes to Me by Arundhati Roy Autobiography/Biography/MemoirNonfiction By the time she won the Booker Prize for her debut novel The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy had already lived several lives. Here, she recounts experiences as a poet, activist, architecture student, and award-winning novelist, but the real magic is in Roy's reflections on the complex and ever-changing dynamics of family, relationships, and ambition. You needn't know a thing about her career to find inspiration and intellectual delight in these pages. - Rebecca Joines Schinsky Buy Now Oathbound by Tracy Deonn Fantasy Book three in The Legendborn Cycle may be Deonn’s best book yet. Bree Matthews will need her perseverance as she learns to wield her powers away from her friends, the Legendborn Order, and her Root magic ancestral elders. Instead, she must trust a dangerous bargain with the Shadow King—a being that would do anything to claim her power. Meanwhile, Selwyn is fighting his Demonia with the only person alive who can help, and Nick is doing everything he can to find Sel and Bree. Oathbound tests the strength of friendships, institutions, and magic as our heroes confront the true cost of power. - R. Nassor Buy Now Old Soul by Susan Barker FictionHorror This outstanding, genre-defying novel will ruin your life but in the best way! Two strangers stuck at an airport in Japan start talking, and eventually discover they have both had someone close to them die who had a connection to the same mysterious woman. One of the strangers, Jake, decides he needs to find everything out that he can about this woman, a journey that takes him all over the globe. But each bit of information he gathers only makes her story more mystifying and alarming. Who is this enigma? Part horror, mystery, and 'OMFG', this upsetting, brilliant novel has an ending that will haunt your days, and you'll thank it for it. - Liberty Hardy Buy Now On Again, Awkward Again by Erin Entrada Kelly and Kwame Mbalia Young Adult Geek out with this younger YA book, which follows two high school freshmen learning how to navigate school, friendship, family drama, and falling in love for the very first time. Pacy and Cecil meet on their first day of school, but neither has it together enough to fess up to their feelings. Both are forced into helping plan the freshman dance, and no matter how much they try to deny what's going on, the sparks only get brighter. The dynamic writing duo behind this book has created two memorable characters who will have you weighing in on their ongoing battle: Star Wars or Star Trek? - Kelly Jensen Buy Now One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This by Omar El Akkad Nonfiction This is more than a book; this is a time capsule recording the visceral horror many of us in the U.S. and Western world at large felt as we bore witness to and were complicit in genocide. Omar El Akkad applied his first-hand experience, historical precedent, and journalistic reporting skills to the war in Gaza and the suffering of Palestinians, stepping away from fiction to write his first nonfiction book from a response that rang out across the digital world: "One day, everyone will have always been against this." This powerful reckoning has become a bestseller and is a finalist for a National Book Award. - S. Zainab Williams Buy Now Queer Enlightenments: A Hidden History of Lovers, Lawbreakers, and Homemakers by Dr. Anthony Delaney Nonfiction Reading this history of queer and gender nonconforming people in the 18th and 19th centuries was at times maddening in how familiar it felt: the moral panic, the cruelty, the self-righteous persecution of people just trying to live their lives. But it was also invigorating to spend time with the 11 fascinating subjects of the book, from more familiar figures like Anne Lister and the Chevalier d’Eon to Mary Jones and Mother Clap. These people were asking themselves a lot of the same questions queer folks are asking today about sex and gender expression, and Dr. Anthony Delaney dives into each of their stories with nuance, tenderness, and care. - Vanessa Diaz Buy Now Rosemary Long Ears by Susie Ghahreman Children's Sometimes, you've got to let your ears down and let your paws get dirty to have a little fun. This sweet picture book follows weiner dog Rosemary and her best human friend through a day of fun around the neighborhood. It's full of puddles, leaf piles, and all kinds of young people taking delight in a day outside. At the end of the day, we see Rosemary and her friend delight in a luscious bubble bath. The art is as bright and lively as the text, making this a surefire hit for young readers–especially those who love a good animal story. This has been a go-to gifting title this year. - Kelly Jensen Buy Now Salt Bones by Jennifer Givhan HorrorMystery/Thriller A perfectly blended family drama with a past and present missing person’s mystery that sinks readers into a small town by the Salton Sea. I was equally invested in Mal and her family—from her mother blaming her for her sister’s disappearance when they were in high school to Mal keeping the father of her teen daughter’s identity a secret—and finding out what happened to the missing women, then and now. Throw in nightmares about a horse-headed woman, a politician brother aligned with the rich, and a race to find another missing person, and this atmospheric mystery is all-absorbing. Bonus: Victoria Villarreal is an excellent audiobook narrator. - Jamie Canaves Buy Now Searches: Selfhood in the Digital Age by Vauhini Vara Nonfiction What does it mean to be a person in a moment when technology is increasingly good at performing humanity? What does it mean to create art and seek connection when algorithms purport to replace both? Vara's attempt to co-write a book with AI ventures to surprising places and achieves a level of nuance that is all too uncommon in today's discourse. Part performance art, part social commentary, this is the book about AI and creativity I’ve been waiting for. - Rebecca Joines Schinsky Buy Now Sky Daddy by Kate Folk Fiction Yes, it's a book about a woman who gets off on planes. Literally. It's one of the ways she divorces herself from her job as a social media content moderator. By all means, Linda tries to appear as normal as possible, but as she grows closer to another person (quite accidentally, in fact!), the cracks in her facade grow bigger and bigger. Can she balance a human relationship with her sexual relationship with airplanes? This book is fresh, it's funny, and it's going to absolutely change how you see airports and airplanes for the rest of your life. 2025 has been flush with excellent weird lit, and this title is among the top. - Kelly Jensen Buy Now So Many Stars: An Oral History of Trans, Nonbinary, Genderqueer, and Two-Spirit People of Color by Caro De Robertis Nonfiction I named this a Best Book of 2025 So Far and had to bring it back for the finale, a collection of beautiful stories of self-discovery, activism, resistance, and survival from queer elders of color. These testimonies are a necessary record of lived experience and hard-won progress, a love letter to queer history, and a reminder of the gift it is to have living elders among us. The joy in each of these stories is what has stayed with me, a joy that persisted even in periods of profound struggle and loss. We hear all the time that joy is resistance; this is the kind of work that really drives that point home and gives me hope for a better future. - Vanessa Diaz Buy Now Startlement: New and Selected Poems by Ada Limón Poetry Pulling from Limón’s six published collections, these gorgeous poems unfold in chronological order from Lucky Wreck to The Hurting Kind. Having read every in-print title by the 24th U.S. Poet Laureate, I found myself electric with excitement to behold some of the prolific author’s new and new-to-me work. Revisiting familiar poems fed my bookish heart in myriad ways, and reading pieces from This Big Fake World and the final section for the first time is precisely why I open books—to connect, to learn, to feel awe. If you need a gift for yourself and for others, look into this exploration of dreams, grief, love, the ordinary, and the extraordinary. - Connie Pan Buy Now Stone Yard Devotional by Charlotte Wood Fiction This meditative novel from Australia quietly landed in the U.S. this year, but it was shortlisted for the 2024 Booker Prize when it first published across the pond. I read it not knowing it was exactly the kind of book I needed, one that made room for rumination in the face of great loss. Following a woman who takes refuge in a religious community, this is a novel about grief and the unexpected ways we process trauma and forgive each other. I had no idea what to expect going into this book but looked forward to picking it up in a way I haven't experienced in a long time. In a loud and frightening world, it became my quiet place to think. - S. Zainab Williams Buy Now Sympathy for Wild Girls: Stories by Demree McGhee Fiction This collection of stories about queer Black women is going to live in my head for a long time. If you love Carmen Maria Machado's work, you need to pick up Sympathy for Wild Girls. They both excel at writing feminist, fabulist/magical realist stories that get under your skin. These stories explore intense, undefined relationships between women; the horror at having a body (especially a racialized, sexualized body); and the strange paths grief can lead you down. Visceral, evocative, and thought-provoking, these are stories that benefit from discussion and deep reading. This collection deserves to be recognized as a new classic. - Danika Ellis Buy Now The Bewitching by Silvia Moreno-Garcia FantasyHorror In 1990s Massachusetts, Mexican grad student Minerva is researching an obscure horror writer who attended the same university decades prior, and the unexplained disappearance of that writer's roommate. The more she learns about both, the more parallels she sees with the unsettling stories her great-grandmother Alba told her about her life in 1900s Mexico, stories of witchcraft and an insidious evil that might now be lurking in the halls of this New England college. SMG stays spinning the genre roulette and going, “Yeah, I can do that.” And y’all, she did that, in deliciously creepy form. - Vanessa Diaz Buy Now The Buffalo Hunter Hunter by Stephen Graham Jones Horror On the third day of reading Jones' latest horror novel, I had a nightmare, but it might not be why you think. The monsters here are supernatural and all-consuming, but the true horror is the very real story that's told of the Marias Massacre, where around 200 Blackfeet were murdered in the dead of winter. The story is told through a journal found in 2012, which was written in 1912 by a Lutheran pastor. The pastor records his time with a Blackfeet man named Good Stab, a man with peculiar eating habits and seemingly superhuman abilities... and revenge on his mind. - Erica Ezeifedi Buy Now The Conjuring of America by Lindsey Stewart Nonfiction Since the beginning of the United States, Black conjure women, who combine traditional West African spiritual beliefs with herbal remedies and local resources, have been a balm to their communities. The legacy of these Mammies, Voodoo Queens, and Reconstruction-era Blues Women began, like so much of American history, in the South during slavery. Here, Feminist philosopher Lindsey Stewart traces their influence and legacy, which includes everything from blue jeans to Vicks VapoRub, to 2023's The Little Mermaid. - Erica Ezeifedi Buy Now The Dry Season: A Memoir of Pleasure in a Year Without Sex by Melissa Febos Nonfiction A memoir about celibacy from a writer whose debut recounted her time working as a dominatrix could seem like a gimmick. In Melissa Febos's hands, it is anything but. Yes, this is a book about a year without sex, but it is really a book about all of the other ways to develop relationships, engage with the world, and find pleasure. In solitude, Febos discovers freedom, time to engage in intellectual and creative pursuits, and needed perspective. In her thoughtful and often surprising reflection, she offers us space to consider our own distractions of choice and what we might find on the other side of them. - Rebecca Joines Schinsky Buy Now The Entanglement of Rival Wizards by Sara Raasch FantasyRomance The Entanglement of Rival Wizards is a stunningly effervescent D&D-inspired queer romantasy. When rival graduate researchers, Sebastian Walsh and Elethior Tourael, collaborate on a prestigious research grant, reluctant respect morphs into passionate love. Sebastian is a human Evocation Magus who thinks he can prank his way out of PTSD, and Elethior is a half-elven Conjuration Magus who hates the family legacy he has to perpetuate to pay for his mother’s long-term care facility. Somehow, Raasch delivers impeccable chemistry, impressive magical research, and a biting critique of the military-industrial complex under capitalism. - R. Nassor Buy Now The Favorites by Layne Fargo Fiction Here's the premise: "Wuthering Heights retelling set in the world of ice dancing." That was all I needed to go all in on this book, but maybe you need more. This tale of Kat and Heath, whose ambitions and obsessions draw them together and push them apart, is as absorbing and toxic as its inspiration. The story is told in a documentary format, which lends itself to a fantastic audiobook. Actual Olympian Johnny Weir narrates the part of a catty gossip blogger, and it's pure magic. If you like your books soapy, gossipy, and delicious, don't miss this one. - Isabelle Popp Buy Now The Ghosts of Rome by Joseph O'Connor FictionHistorical Fiction In Nazi-occupied Rome, the Choir works to smuggle POWs, Jewish people, and other allies out of Nazi hands. But tensions are rising as known members of the Choir are cooped up in the Vatican and under surveillance by the SS, and a man's unexpected arrival threatens the entire operation. But one woman is committed to the Choir’s cause at any cost. Contessa Giovanna Landini goes head-to-head with the number one enemy of the Choir, the SS commander charged with taking the operation down. It's a book made all the more timely as masked men grab people off the streets of my beloved Chicago. Doing the right thing is hard and often full of sacrifice, but it's the only way forward. - Elisa Shoenberger Buy Now The Isle in the Silver Sea by Tasha Suri FantasyRomance This book skyrocketed to the top of my personal best-of list as not only one of my favorite books of the year but one of my favorite books of all time. It explores the very heart of what it means to tell—and retell—stories. Simran and Vina know that meaning all too well as characters in a world where stories play out over and over again, reincarnated to live out the same tale across the centuries. But, much like in real life, the stories affect far more than just the characters within them. Five stars? I would give this book every star in the sky and then some. Simran and Vina have my heart. - Rachel Brittain Buy Now The Leaving Room by Amber McBride FantasyYoung Adult This novel in verse offered such a thoughtful and unique take on the afterlife. It reminded me of how I felt reading Gabrielle Zevin's Elsewhere as a teenager but for today's generation. It stars Gospel, a Keeper who guides recently deceased souls from life to what comes next. But when she meets another Keeper named Melody, they work together to find a way out of the Leaving Room. - Andy Minshew Buy Now The Macabre by Kosoko Jackson FantasyHorror Lewis is a struggling Baltimore artist grieving the loss of his mother, and he's in London for a curated art exhibit at the British Museum—or so he thinks. The exhibit is a ruse; he’s really there for a test to see if the fugue-like state he enters while painting is actually magic that can be used to enter nine paintings scattered across the globe, sinister paintings that are the work of Lewis’s great-grandfather and must be recovered at all costs. So begins this time-hopping, globe-trotting horror fantasy adventure into art history, Gothic magic, and cursed objects. It’s a gorey romp, a history lesson, a queer romance, and a damn good time. - Vanessa Diaz Buy Now The Nine Moons of Han Yu and Luli by Karina Yan Glaser Children's This gorgeous, expansive middle grade historical fiction delves into Chinese history through two alternating timelines. As Han Yu traverses ancient China with a poet to sell goods for his ill family, Luli launches a museum to aid her family during the Great Depression in Chinatown, New York City. These two tweens use courage and creativity to support their families, their two storylines becoming increasingly interconnected as the novel progresses. It’s an action-packed and heartwarming read, steeped in richly imagined worlds that are as well-researched as they are fascinating. - Margaret Kingsbury Buy Now The River Has Roots by Amal El-Mohtar Fantasy This book became an instant favorite for me as soon as I read it, and it’s still my favorite read of 2025. It’s the story of two sisters living near a river, a boundary between our world and another, more magical one. When a terrible tragedy befalls one sister, the other is determined to find justice. To get it, she’ll need to traverse liminal worlds, face down magical threats, and try to retain some semblance of who she is. - Chris M. Arnone Buy Now The Scammer by Tiffany D. Jackson Mystery/ThrillerYoung Adult I was still preaching the gospel of The Weight of Blood when I got around to reading The Scammer, and let me tell you, Tiffany D. Jackson does not, cannot miss. I was engrossed from the moment I saw where this story was headed (it's inspired by the events surrounding the Sarah Lawrence cult, but set on an HBCU campus), and the ending left me in open-mouthed appreciation of a well-executed twist. If you like suspenseful books set on college campuses, explorations of cult dynamics and manipulation, and stories ripped from the headlines, you're going to want to read this one now. - Vanessa Diaz Buy Now The Wilderness by Angela Flournoy Angela Flournoy's first book, The Turner House, is a fantastic novel about a family, and this follow-up is a masterful work about 20 years of friendship between Black women, who are every bit a family as well. Over two decades, January, Monique, Nakia, and Desiree traverse school, love, loss, career changes, location changes, and all the in-jokes, silliness, disagreements, and fierce loyalty that come with long friendships. Each of their paths is filled with hurt and happiness, and the novel shares their lives in dazzling sections that speed toward an ending that will break your heart. (I highly recommend the audiobook version.) - Liberty Hardy Buy Now This Is the Only Kingdom by Jaquira Díaz Fiction With a focus on mother-daughter relationships, this is a deeply felt, layered generational drama and coming-of-age novel. Maricarmen’s life changes as a teen in Puerto Rico when her mom throws her out after overhearing her confess her love for a boy she was forbidden to date. Decades later, her daughter Nena finds herself in Miami trying to understand generational trauma. This was one of the very few 2025 releases that I was highly anticipating that actually delivered, and just like Díaz’s memoir, I felt this book inside my bones. Almarie Guerra does a fantastic job narrating the audiobook. - Jamie Canaves Buy Now This Place Kills Me by Mariko Tamaki, illustrated by Nicole Goux ComicsGraphic NovelMystery/ThrillerYoung Adult This sapphic YA graphic novel takes place in the '80s, but its story of teenage alienation is timeless. Wilberton Academy's resident It Girl, Elizabeth Woodward, is found dead the morning after she starred in the school's rendition of Romeo and Juliet. She's said to have died by suicide, but something about that doesn't feel right. Outcast Abby Kita is determined to find out what really happened to one of the few girls at Wilberton who was ever nice to her. Turns out, Elizabeth had secrets—secrets that might have gotten her killed. - Erica Ezeifedi Buy Now To the Moon and Back by Eliana Ramage Fiction Debut author Eliana Ramage shows as much ambition as her starry-eyed protagonist in what I’m already sure will be my favorite book of the decade. Steph knew from the first moment she looked through a telescope that she wanted to become the first Cherokee astronaut. But reaching her goal means making sacrifices, ones that seem to get bigger with each step she takes toward her objective. We follow Steph across decades as she shoots for the moon, with forays into the perspectives of her mother, sister, and other women who shape her journey. It’s an astonishing book about Indigenous communities and what it really takes to achieve big dreams. - Susie Dumond Buy Now Truth Is by Hannah V. Sawyerr Young Adult Truth is entering her senior year without a clear idea of what she wants for her future. She loves poetry, and while she doesn't love having to tiptoe around her mother, sneaking to weekly poetry classes has given Truth an outlet she so desperately needs. Her life becomes more complicated when she finds herself pregnant and must navigate the ever-changing landscape of abortion services. But this isn't just a story about Truth's challenges. It's a story about her finding her voice, sharing her voice, and owning what her own future looks like. This verse novel is moving and heartfelt, and Truth is an unforgettable character. - Kelly Jensen Buy Now Tusk Love by Thea Guanzon FantasyRomance Looks like I'm on board the romantasy train! I'm a big fan of Critical Role, so I had to try this novel that started as an in-universe romance book in their D&D game. Guinevere is a sheltered merchant's daughter with suppressed magical powers. Oskar is her reluctant half-orc protector on the road. Their undeniable chemistry upends all their plans. I was pleasantly surprised to find that not only is Tusk Love great for Critical Role fans, but it also stands alone as a steamy read that is somehow simultaneously tongue-in-cheek and heartfelt. It's delightfully slowburn and spicy: they're quick to sleep together and slow to admit their feelings. - Danika Ellis Buy Now We Do Not Part by Han Kang Fiction Literary fiction of the highest order from a Nobel Prize-winning novelist. Not much happens in this quiet, dream-like novel that asks rich questions about history, memory, connection, and pain. It's the rare book that can be equally subtle and unsettling, and that's evidence of a masterful writer working at the height of her powers. You always know you're in good hands with Kang, and that makes it a pleasure to follow her wherever she wants to go. - Rebecca Joines Schinsky Buy Now When the Tides Held the Moon by Venessa Vida Kelley FantasyHistorical FictionRomance Fantasy! Romance! Historical Fiction! Found family! Gorgeous art! Venessa Vida Kelley’s dreamy debut When the Tides Held the Moon has something for everyone. Puerto Rican blacksmith Benny is tasked with building a giant glass tank. When he delivers it to the 1910s Coney Island carnival sideshow that commissioned it, he realizes it was constructed for a real merman captured from the East River. And when he falls in love with that merman, Benny realizes he’s constructed his prison and now must find a way to help him escape. The ensemble cast of “human curiosities” and Vida Kelley’s vivid illustrations make this story truly shine. - Susie Dumond Buy Now Wild Dark Shore by Charlotte McConaghy Fiction Dominic Salt and his three children are in charge of Shearwater island, an arctic, isolated place that harbors the world's biggest seed bank. As climate change takes its toll, fewer scientists visit. When a woman named Rowan washes ashore, the mystery of her appearance and her own mission to unpack the family's secrets both draw out over the strange, remote locale. McConaghy, author of 2020's Migrations, has become a singular author of our moment, writing climate fiction that is packed with rich humanity, at its best and worst. Her newest will break your heart into little pebbly pieces, and I mean that as the highest of compliments. - Leah Rachel von Essen Buy Now

This is a moderated subreddit. It is our intent and purpose to foster and encourage in-depth discussion about all things related to books, authors, genres, or publishing in a safe, supportive environment. If you're looking for help with a personal book recommendation, consult our Weekly Recommendation Thread, Suggested Reading page, or ask in r/suggestmeabook.

/r/Books End of 2025 Schedule and Links

- books

Welcome readers, The end of 2025 is nearly here and we have many posts and events to mark the occasion! This post contains the planned schedule of threads and will be updated with links as they go live. Start Date Thread Link Nov 15 Gift Ideas for Readers Link Nov 22 Megathread of "Best Books of 2025" Lists TBA Dec 13 /r/Books Best Books of 2025 Contest TBA Dec 20 Your Year in Reading TBA Dec 30 2026 Reading Resolutions TBA Jan 18 /r/Books Best Books of 2025 Winners TBA submitted by /u/vincoug [link] [comments]

Weekly FAQ Thread November 16 2025: What is your favorite quote from a book?

- books